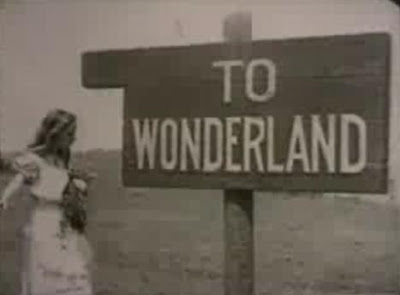

Some stories beg to be filmed. I’ve seen five versions of Alice in Wonderland—two of them silent—with at least ten more to go. That’s just movies, mind you; not TV. The appeal of the story seems simple enough: a children’s classic with hidden depths; compelling to kids and their parents alike; humorous and frightening in turn… and profoundly weird, in a mostly visual way that leaves f/x pioneers licking their chops, generation after generation. Alice has infinite potential, it seems; so much so that no one adaptation has eclipsed its fellows the way The Wizard of Oz did all others, before and after 1939. There will always be room for another Alice. The 1915 version, alas, makes you grateful.

It was during the mid-teens that silent film left its theatrical trappings behind. Editing advanced; some directors began moving their cameras in earnest; close-ups humanized characters and freed powerful archetypes from the boundaries of the dumbshow. The days of the ‘fixed camera’ were numbered. Now, I’ve used this space to argue, more passionately than most, that some of those fixed-camera films were brilliant—worthy of praise they rarely receive. In the hands of men like J. Searle Dawley or Georges Méliès, for example, fixed camera films merged theatrical and cinematic techniques in provocative ways. But they were geniuses, and W.W. Young was not. Young, by 1915, should have known that a stationary camera requires accelerated pacing and dynamic set pieces to maintain viewer interest. His Alice has neither—its scenes plod and its star, Viola Savoy, plods too, seemingly killing time in a film with too much time already. His sets remind me less of Wonderland than my aunt’s backyard garden, and really, my aunt’s first love is dragonboating.

What will you like about Alice in Wonderland? Probably the costuming: a set of garbs and masks ranging from the broadly cartoonish to early Punch-like caricatures to, in a few cases, the photorealistic. In the last case I’m thinking of the Komodo Dragon that slithers convincingly over rocks near Alice’s feet, or the Dodo, who looks precisely like a textbook rendering of same, except for the walking stick. These are actors in suits, but the effect is darker than Disney World. Most disturbing—and dissonant—is the White Rabbit; a suited fellow with a very accurate rabbit’s head, except for the eyes, which narrow with disapproval like an angry man’s, and hands which, for some reason, are the bare hands of the man in the costume. Seeing the addled Rabbit wring his human hands is a creepy thing, and I suppose the best thing about this otherwise uninspired film.

It’s like watching your kid’s Christmas pageant, you know? The costumes are the best part. And even if the kids are inept, it’s OK—watching them stumble around on stage, slightly lost, is cute. But in Alice, it’s not cute—it’s just boring. And clumsy. “The croquet-balls were hedgehogs, the mallets were flamingoes and the arches were soldiers,” an intertitle tells us, prior to the scene in question. Should such a description be necessary? In this case, it helps.

At 52 minutes, Alice in Wonderland still feels long. It also feels incomplete, if only because certain standard episodes from the book are missing. The Mad Hatter makes an appearance late in the film, but we never see his tea party. Alice grows and shrinks, but never on camera—we only know it by observing Savoy next to various pieces of undersized furniture. Young could have made it happen. The first Alice, filmed in 1903, portrayed it just fine.

My DVD print of Alice in Wonderland is accompanied by a fairly generic piano score, and I think my final thoughts about the film are best summed up with a musical recommendation to any future accompanists out there: ‘go weird or go home.’ I’m an opponent, normally, of scores that treat silent film as object rather than subject—something alien, to be played at rather than with, but Alice is not a gripping piece of art on its own. What it is, is odd; even disturbing to look at, and should be odd to listen to. Do it, maestros. Otherwise, it won’t just be Alice Liddell taking a nap.

Where to find Alice in Wonderland:

My copy of Alice in Wonderland can be found along with three other versions on one DVD: Alice in Wonderland: Classic Film Collection, distributed by Infinity Entertainment Group.

And thanks to Caren Feldman of the Toronto Film Society, who was generous to lend me this DVD, even if I didn’t like it. ;)

HA! Maybe first time round made it more amusing. Caren

ReplyDeleteHighly likely.

ReplyDelete