Can you guess what this one’s about?

At 33 minutes, Alice Guy’s The Birth, the Life and the Death of Christ was a healthy length for the time, and probably felt more epic in 1906 than it does now. We might focus on its limitations: the fixed camerawork, typical of the era, and the deliberate stagecraft, which makes The Birth seem like a theatre production with a lens for an audience. God help the viewer who doesn’t know the story going in, since Guy bypasses considerable and complicated details to tell the story in pantomime. We miss some of the best parts, too. We never see his fabled throwdown with the moneylenders, or his admonition against those who would throw stones. In the absence of any dramatic tension (we all know how this ends), it is the writer and/or director’s interpretation of Jesus that makes a film about him interesting. Guy, however, is content to depict—and the man she depicts is one-dimensional, even by mytho-heroic standards.

And yet the film still worked for me. Like many movies of the pre-Griffith period, The Birth’s sheer phoniness inspires an intriguing, and occasionally unnerving, take on a very old tale.

Guy couldn’t have looked to many previous films for inspiration. She would have turned to painting, sculpture, and the stage. However, these mediums depict people and events in much more abstract fashion than camera lenses did in the early days. The result is images like Guy’s angels: heavenly denizens dressed identically in white robes, each with a pair of sharply tapered wings, fixed in one position.

The effect is unconvincing, but it does evoke artwork that is very old, venerable, and sacred in feel:

Giotto, Annunciation—The Angel Gabriel Sent by God (1306)

Whereas the angels depicted by Giotto and earlier painters had their wings fixed in place because paint can’t move, Guy made the conscious choice (albeit, the easier one) to keep that immobility while allowing the angels themselves to fidget and wander. The presence of this classical form in a (for the time) hyper-realistic setting makes everything look fake... or, unearthly.

Another example: ‘Nativity and Arrival of the Magi.’ In this sequence, Balthasar, Caspar, and Melchior arrive at the site of Jesus’ birth and, just as we’ve come to expect from every Christian-themed holiday special and Christmas pageant performed in our own lifetimes, they bear their gifts before their infant Lord, paying fealty to him.

But this is unlike a stage production, where the baby would be represented by a doll, or perhaps a flashlight beaming upward from the base of a crib. Guy uses a real baby, probably a boy about one year old, squirming, bouncing and waving his arms before his subjects, just like any kid that age would do. And since Guy never zooms or pans her camera during the scene, we are left watching grown men prostrate themselves before an infant who is oblivious to what is around him. That is how it would have really looked, I guess, but only now do I realize how hard most directors and artists work to make it seem less strange.

Guy also shocks us with the ‘Saint Veronica’ scene, in which the eponymous woman mops Jesus’s bleeding brow with a cloth as he bears the cross past her. As Jesus exits the frame, the actress opens the cloth to reveal an image of Jesus’s face. Guy cuts to a closeup of the same woman, holding the cloth against a blank backdrop. Seeing the painterly image of Christ’s face on the cloth—looking nothing like a bloodstain—is strange enough; leaving the film’s universe altogether to emphasize it is stranger still. In this moment The Birth feels like a sermon, or maybe that moment of surprise when a faith healer bids a crippled man to rise, and he does, and we feel we ought to applaud. Showmanship, amid the sacred.

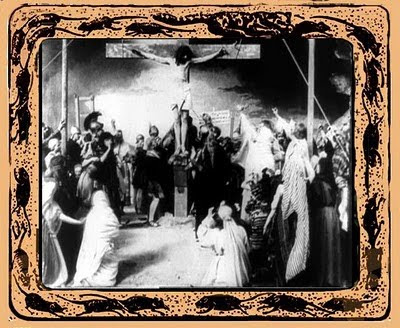

Like almost every sequence in The Birth, this one is entirely self-contained. Only once does one of Guy’s intertitles actually break the action, and the moment is surprisingly jarring. ‘The Crucifixion’ ends with Christ suspended on the cross, in the middle of the frame. The next scene, ‘The Agony,’ opens to the same visual, with all the actors in virtually the same positions. The only difference is that they look tired. This may not seem like much, but it shows Guy’s willingness to suggest the passage of time without simply letting the camera run on in real-time (a habit that makes some films of this period very dull).

The Birth, the Life, and the Death of Christ ends in the tomb, as it must. The medieval angels return, wings freshly starched, and remove the lid of Jesus’s sarcophagus, which appears to weigh all of 25 pounds. Guy doesn’t have Jesus climb out of the stone box here; rather, the actor’s image is superimposed over it, hovering in a pose of ascension—again, drawn from classical painting, but ending with a sudden disappearance that only a movie camera can produce.

I find this last sequence to be more subtle and moving than the rest. Maybe because the effect is so seamless. Or maybe because in this scene, unlike so many others, Guy let her creativity take over. Tasked with depicting the weirdest, most unnatural moment of all, she chose abstraction, and not through the techniques of older artforms, but those of her own.

Where to find The Birth, the Life and the Death of Christ:

La Naissance, la vie et la mort du Christ appears on Disc One of Kino International’s Gaumont Treasures (1897 to 1913), which is devoted to Alice Guy’s work alone. Discs Two and Three examine the work of Louis Feuillade and Léonce Perret, respectively. It’s a terrific set.

No comments:

Post a Comment